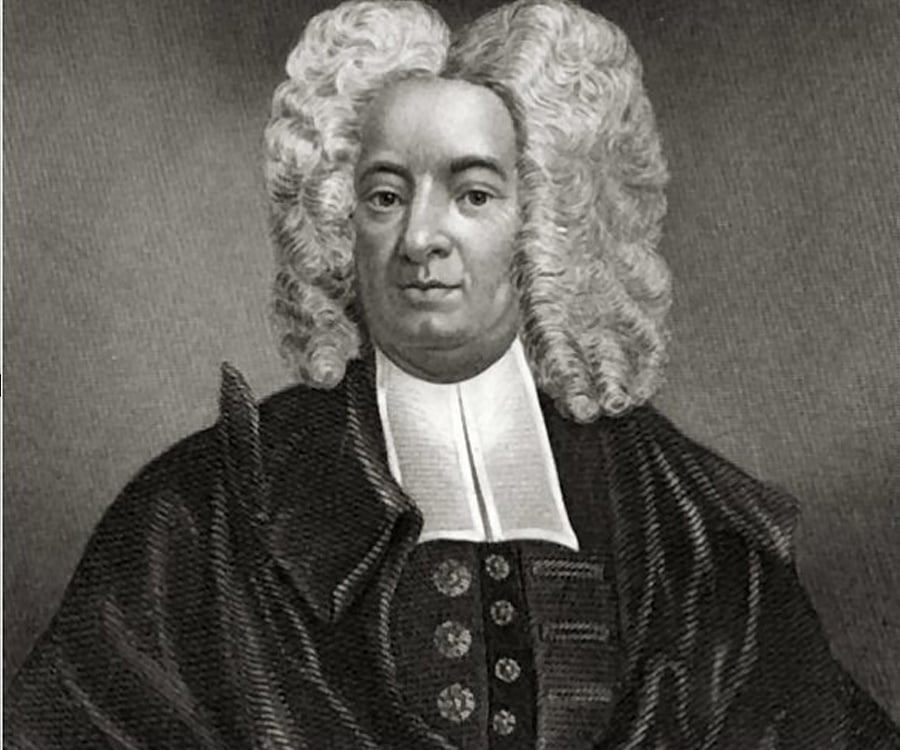

All of Life Under Christ: The Godly Ambition and Perseverance of Cotton Mather

The year was 1674. At the time, acceptance to Harvard University was conditioned upon writing a persuasive entrance essay — in Latin. Yet it was in this year that, at just 11 and a half years of age, Cotton Mather would be accepted as Harvard’s youngest student. He would go on to receive a Bachelor’s degree at only 15, and a Master’s at 18.

Who was Cotton Mather? The son of Increase Mather, a famous New England puritan, Cotton was undeniably a prodigy. His exceptional giftedness was evident to all. In his lifetime, Mather wrote more than 400 published works. He was a prolific wordsmith, having mastered seven languages! He wrote books on theology, history, science and medicine. He wrote works of fiction and essays on practical piety. He edited and republished the first Psalter ever printed in North America. He cataloged the flora and fauna of Massachusetts Bay. He corresponded with medical doctors trying to develop cures for the smallpox disease. His book, Essays to Do Good, was monumental in inspiring works of charity and mercy throughout the American Colonies.

Mather was passionate about studying both God’s word and God’s world. He saw every domain of knowledge as subject to the Lordship of Jesus Christ. He wrote, "Let every branch of learning and science be humbly made serviceable unto our Lord Jesus; and let Him be honoured, with the bringing in of every sheaf, as well as of the first fruits of our labours."1 He elsewhere wrote, "All arts and sciences, all schemes and enterprises, have a worth that is derived from Christ."2

Cotton Mather was therefore very passionate about Christian education, most importantly the education of his own children. He once remarked, “If no other a task were to present itself in my life than this, the education of my children is enough to do honor to the gospel.”3

Yet Cotton’s interest in Christian education extended far beyond his own children. He often gathered and shipped out helpful resources for poor and struggling ministers serving on the frontier. At one point, Cotton calculated that he was giving away nearly 600 books every year for free.4

What drove Cotton Mather to be so diligent and industrious throughout his life? Was he working under a yoke of self-righteousness, trying to earn his right standing before God? Far from it! Mather echoed Luther in stating that justification by faith alone is "the article of the standing or falling of the church."5 Mather wrote, "The grace of the gospel is a free and undeserved gift of God, given to us through faith in Jesus Christ. It is not something that we can earn or merit, but is offered to us out of God's infinite love and mercy."6

Yet Mather also confessed, rightly, that those who have been truly saved by this free grace will be a transformed people. He elsewhere wrote, "The grace of the gospel is a powerful grace, that enables us to overcome sin and temptation, and to live in obedience to God's commands. It gives us strength and courage to persevere in the face of trials and adversity."7

For Mather, the virtue of perseverance in the face of trials and adversity was far from theoretical. His first wife, Abigail, with whom he had nine children, died along with two newborn twins and a two year old daughter when smallpox struck the Mather household. He later remarried a godly widow named Elizabeth, with whom he had six more children. Yet she, too, passed away. He was married a third time to Lydia, the only wife who outlived him. He had fifteen children in all, nine of whom died in infancy. Four more died from disease or drowning in early adulthood. During his lifetime, he buried all but two of his own children!

Yet even through repeated, heartbreaking loss, Mather trusted in God’s goodness. His diary entries reflect not a cold, fatalistic stoicism, but a sincere, Godward trust in the midst of immense grief:

- "My heart is as heavy as lead, my dear child is no more. The Lord is righteous in all His ways, and holy in all His works, but how hard it is to see so lovely a flower as this cropt down!" (from Mather's diary entry on the death of his son, Samuel)8

- "I trust the Lord will support me under my affliction, and help me to glorify Him in it. O that I may improve this dispensation, so as to have a happy meeting with my dear child in the morning of the resurrection!"" (from Mather's diary entry on the death of his daughter, Abigail)9

"I lost my dear wife, a most excellent, helpful, and lovely companion, by the small-pox, a disease which she caught by her compassionate attendance upon her children who had it before her. I was sometimes almost overwhelmed with sorrow; but my heart was comforted with the grace of God, and the sweet promises of His gospel… The Lord has taken from me the desire of my eyes with a stroke, but I trust He will support me under it, and sanctify it to me. I will look to Him who has said, 'I will never leave thee nor forsake thee.' I will hope in Him, and wait for Him, and expect to see her again in a better world.” (from Mathers diary entry after the passing of his first wife, Abigail)10 - "The Lord gave, and the Lord hath taken away, and blessed be the name of the Lord. She is now with Christ, which is far better than any enjoyment of her here below. Blessed be the Lord, that ever I had such a jewel to enjoy, and blessed be the Lord, that ever He made such a saint to shine upon us." (from Mather’s diary entry on the day of his second wife Elizabeth's death)11

- "The Lord has afflicted me very sorely, but I desire to be humbled under His hand. Blessed be God, I have not only submitted to the Lord's will, but I have been comforted with the thoughts of His wisdom and goodness in what He has done." (from Mather's diary entry on the death of his son, Nathaniel)12

Few saints in history have left us a better example of suffering well than Cotton Mather. Most of us will never endure the level of loss he endured, yet all of us will face suffering in this life. Westmount, will we imitate Cotton Mather as he imitated Christ?

It is also doubtful that many, or any of us, will have giftings in areas as wide and varied as Cotton Mather. Not every servant has been given the same number of talents (Matthew 25:14-30.) Still, his example of taking every thought captive to the obedience of Christ calls out to us to be faithful in the spheres with which we have been entrusted. In whatever we study, in whatever we teach, in whatever we do, let us seek to live all of life according to the mind of Christ!

As Mather himself so aptly put it, "In every province of nature, in every range of learning, Jesus Christ hath claims upon us. To be walking with Jesus Christ in every enterprise is to be walking with Him in the way of truth, and this is to be walking with Him in the way of happiness."13

________________________________________

1. Smith, John. The Role of Christianity in Early American Education. Journal of American History 95, no. 2 (April 2008): 356-357.

2. Mather, Cotton. The Christian Philosopher: A Collection of the Best Discoveries in Nature, with Religious Improvements,"Boston: T. Fleet and T. Crump, 1720.

3. Grant, George. Cotton Mather (Lecture). 5th Annual History Conference, 2000. Wordmp3.com.

4. Pickowicz, Nate, and Benge, Dustin W.. The American Puritans. Reformation Heritage Books, 2020.

5. Mather, Cotton. The Christian Philosopher.

6. Mather, Cotton. Magnalia Christi Americana, vol. 1. London: Thomas Parkhurst, 1702.

7. Mather, Cotton. The Christian Philosopher.

8. Mather, Cotton. Diary. Edited by David Levin. New York: Arno Press, 1972. Entry dated May 16, 1691.

9. Ibid, Entry dated June 28, 1700.

10. Mather, Cotton. Diary. Edited by Worthington C. Ford. 2 vols. New York: Burt Franklin, 1969. Volume 1, entry dated October 10, 1702.

11. Mather, Cotton. Diary. Edited by David Levin. Entry dated October 13, 1713.

12. Mather, Cotton. Diary. Edited by Worthington C. Ford. 2 vols. New York: Burt Franklin, 1969. Volume 2, entry dated June 12, 1728.

13. Mather, Cotton. The Christian Philosopher.[1]