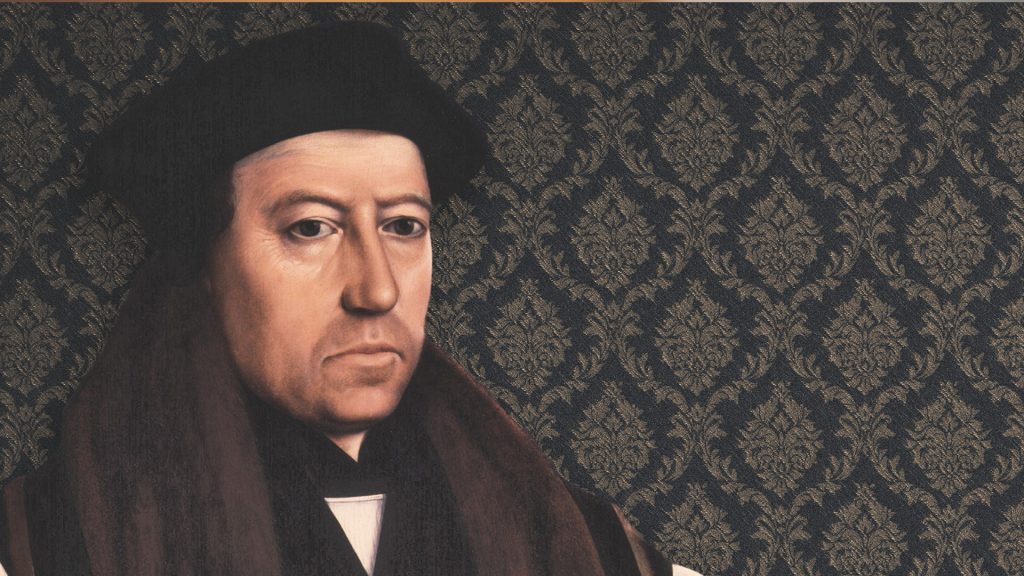

Courage Restored: The Final Testimony of Thomas Cranmer (Part I)

In 1533, in the midst of tremendous social and political upheaval, Thomas Cranmer found himself promoted to England’s highest ecclesiastical office. As Archbishop of Canterbury, he was now the primary spiritual leader of the English church. But the Church of England was in the process of separating from communion with Rome. They would no longer recognize the supremacy of the Pope.

Setting the Stage: Henry VIII Defies the Pope

At that time, the reigning monarch in England was Henry VIII. He was the reason for this tumultuous breakup. The primary issue centered around the legitimacy of Henry’s marriage to the Spanish Princess, Catherine of Aragon. Catherine had originally been the wife of Henry’s older brother, Arthur, who tragically died just 5 months into their marriage. This marriage of Arthur and Catherine had been seen as crucial for maintaining a peaceful alliance between England and Spain. But with Arthur dead, things looked a bit more precarious. It was forbidden by canon law for any man to marry a woman who had been his brother’s wife. But Rome was in no mood to let principle triumph over politics. The Pope at that time, Julius II, granted a special dispensation, an exception that allowed Henry VIII to marry his brother’s widow, preserving the English-Spanish alliance.

But as the years passed, and Catherine failed to provide Henry with a male heir, he grew increasingly anxious about their marriage. The original canon law forbidding marriage to a brother’s widow had a proof text that struck terror into Henry’s heart:

“If a man takes his brother’s wife, it is abhorrent; he has uncovered his brother’s nakedness. They will be childless.” (Leviticus 20:21)

Was God punishing Henry for marrying his late brother’s wife? Was this union even legitimate in God’s eyes? Henry wrote to Pope Clement VII seeking an annulment. The Pope refused, not wanting to contradict the judgment of a previous Pope. And so it was that Henry determined that since the Pope would not grant an annulment, he would no longer submit to the authority of the Pope.

It’s difficult to say whether King Henry was really acting out of conviction at this point, or whether he was just trying to get his papers in order so that he could legally marry Anne of Boleyn, whom he thought could provide him with a son. Most historians favor the latter view, and all agree that whatever was going on in Henry’s heart at that point, his quest for a male heir would spiral into an utterly sinful obsession later in life.

But at any rate, let’s get back to Cranmer. The main takeaway from this mess was that Cranmer became convinced that Pope Julius’ original dispensation granted to Henry was unscriptural. And if the Pope could be wrong on this point, Papal Infallibility had to be thrown out the window. Cracks were forming in Cranmer’s doctrine that would eventually become fertile ground for seeds of change, not only in Cranmer’s theology, but in all of England.

Cranmer’s Reformation

Cranmer now found himself near the helm of the newly independent Church of England. It was a state church, with King Henry as head, and a host of other bishops in varying degrees of episcopal rank. Biblically, the situation was far from ideal! King Henry was no friend of Rome, but neither was he a friend of the doctrines of grace taught by the continental reformers. Most English bishops could be best described as Anglo-Catholic. The churches held a Latin Mass, the scriptures were inaccessible to the common man, and the simple message of salvation by grace through faith in Christ alone was scarcely heard in the land. It was during this time that the “Protestant” King Henry even had William Tyndale burned at the stake for translating the Bible into English!

Cranmer, however, was beginning to grasp the simplicity and truth of the gospel. He understood that Rome’s doctrine, and the doctrine being proclaimed throughout England, was a false gospel, because it robbed God of His due glory:

“This proposition – that we be justified by faith only, freely, and without works – is spoken in order to take away clearly all merit of our works, as being insufficient to deserve our justification at God’s hands; and thereby most plainly to express the weakness of man and the goodness of God, the imperfectness of our own works and the most abundant grace of our Saviour Christ; and thereby wholly to ascribe the merit and deserving of our justification unto Christ only and his most precious blood-shedding. This faith the Holy Scripture teacheth; this is the strong rock and foundation of Christian religion; this doctrine advanceth and setteth forth the true glory of Christ, and suppresseth the vain-glory of man; whosoever denieth this is not to be reputed for a true Christian man, nor for a setter-forth of Christ’s glory, but for an adversary of Christ and his gospel, and for a setter-forth of men’s vain-glory.”[1]

But what was Cranmer to do? He tried to institute reforms in the church, but was regularly thwarted. The King above him, the bishops below him, and the English people around him largely remained staunch in their Anglo-Catholicism. There were some exceptions to this general trend, of course. Two clergymen in particular, Hugh Latimer and Nicolas Ridley, were a great encouragement to Cranmer in his newfound reformational convictions. These men boldly proclaimed the truth of the gospel, and Cranmer promoted them to positions of prominence within the Church of England. Yet wide-scale reform of the church, at this point, appeared to be a political impossibility.

The answer to Cranmer’s impasse came along with the answer to what had been William Tyndale’s final prayer a few years prior. When Tyndale was Martyred in 1536, his dying words were, “Lord, open the King of England’s eyes!”[2]

In 1538, through a bizarre set of political circumstances that can only be described as providential, King Henry approved the printing of the Bible in English, requiring that a copy of the Scriptures be present in every church of the land! The publication and distribution was completed by 1539. For the first time, the English common people had unprecedented access to the Word of God. Even though Cranmer could do very little from the top-down, God’s Word was doing a mighty work, changing the hearts of everyday Englishmen from the bottom-up!

King Henry died in 1547, and was succeeded by his very Protestant son, Edward VI. With less royal interference, a more biblically literate populace, and a greater number of like-minded clergy than ever before, Cranmer was finally able to achieve wide scale reformation in the Church of England. He set up a set of Protestant doctrinal standards known as the 42 Articles, revised the liturgy of the churches, and changed the language of church services from Latin to English, allowing the people to freely hear the preaching of God’s word. He repudiated the doctrine of transubstantiation, the idea that Christ is continually sacrificed in the Lord’s Supper as the elements are transformed into His literal body and blood. He rather maintained that Christ is spiritually present with His people as they remember Christ’s once for all sacrifice for sins.

The cause of English Reformation was growing by leaps and bounds! But then, tragically, Edward died.