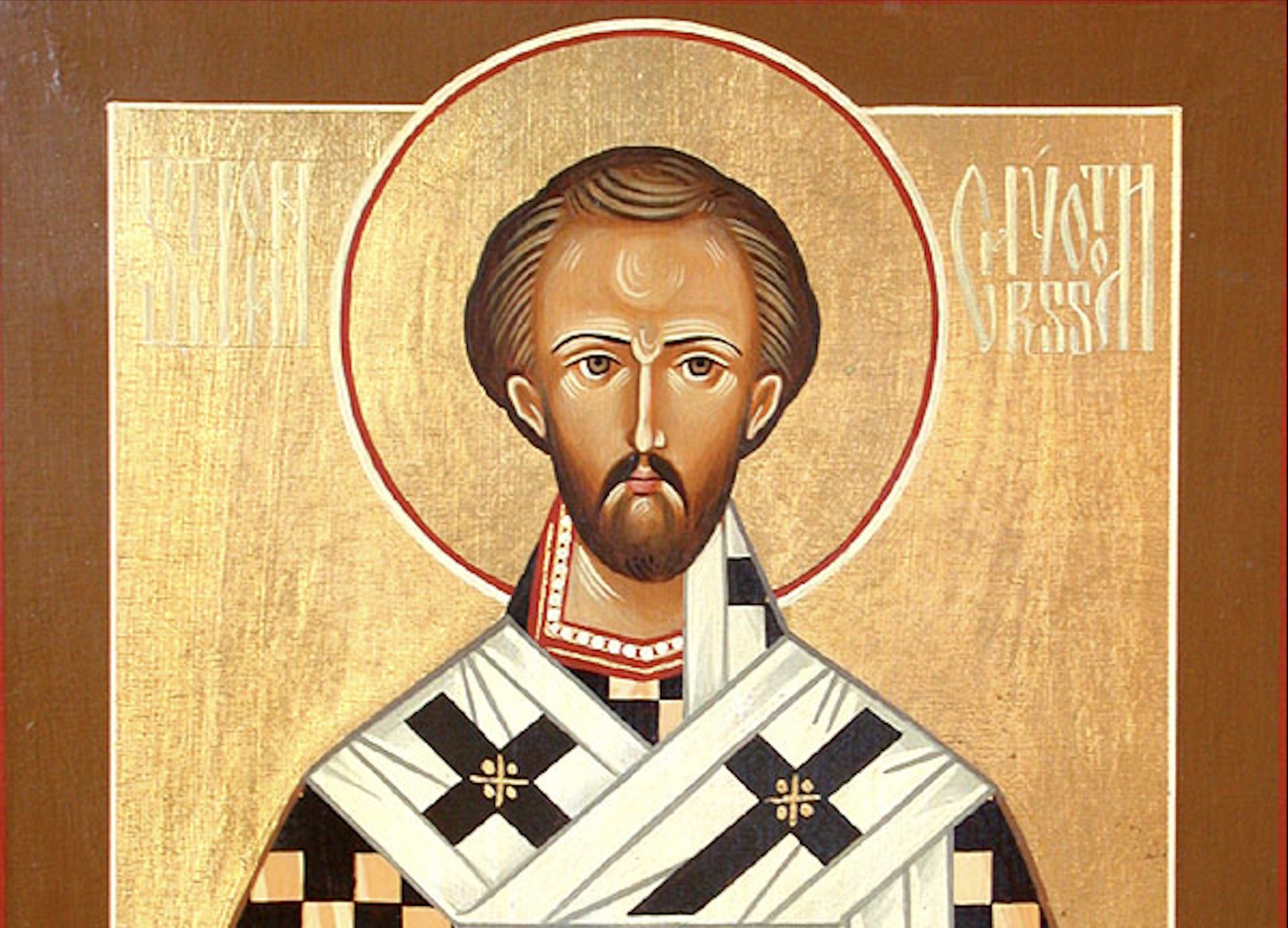

John Chrysostom: The Golden-Mouthed Preacher

When we think of the greatest preachers of church history, some names immediately come to mind. From Luther, Calvin, Knox, Whitefield, and Spurgeon, many of the most renowned and impactful preachers were heirs of the Protestant Reformation. But what if I told you that one of Christianity’s greatest preachers lived more than a thousand years before that time, long before Rome’s errors which precipitated the Reformation had even come into full bloom?

Early Life

John of Antioch, later known as John Chrysostom, was born in 347 AD. Sadly, John’s father, a high-ranking military official, died shortly after he was born. His widowed mother, Anthusa, a devout Christian, devoted herself to his upbringing. John received a first-rate classical education, with special emphasis on rhetoric. This training would serve him well for his calling later in life.

Servant of the Church in Antioch

Following his formal education, John devoted himself to a season of intense personal study of the scriptures, memorising much of the Old and New Testaments over two years. During this time, he lived as a hermit and engaged in various ascetic practices, which took a great toll on his physical health. After this time, John returned to a more balanced lifestyle and set himself to work serving the Church in Antioch. He served as a reader, then a deacon, and was ordained a bishop in the year 386.

John’s preaching was straightforward and eminently practical. He eschewed the fanciful allegorical handlings of scripture which were increasingly common in his day, opting instead to simply exposit the plain sense of the text. As a result, his preaching was not only faithful but very accessible to the common people of Antioch. It was due to his readily apparent giftings in the pulpit that John later became known as Chrysostom, meaning “golden mouth”, his words always being so fitly spoken.

Abducted to Constantinople

John’s reputation as a preacher in Antioch gained widespread renown throughout the Empire, attracting the attention of the Imperial Court in Constantinople. “Why should Antioch have the best preacher in the empire?” they thought. Incredibly, in 398, they sent a contingent of soldiers to Antioch to abduct John and forcibly appoint him as their bishop!

John agonized over being taken from his home and the people in Antioch for whom he so deeply cared. Finally, however, Chrysostom came to see this abduction as the hand of Providence. God had set him in a place of prominence for such a time as this. He resolved to steward the position well, no matter the cost.

Practical, Pointed Application

Constantinople’s ruling class soon found out that by abducting Chrysostom as their Bishop they were going to receive more than they bargained for. Chrysostom’s ministry reflected his conviction that true preaching must not only teach the word but also apply it. And while Chrysostom’s preaching was in many ways golden, it was in no wise yellow! Chrysostom boldly applied the word of God to the issues of his day, regardless of who might take offence. Much of the ruling class did not take kindly to having their pet sins rebuked from the pulpit. Repeatedly, Emperor Aracdius, and especially his wife, Empress Eudoxia, expressed great displeasure with certain aspects of Chrysostom’s pointed preaching.

Twice Exiled

By the year 403, Empress Eudoxia could no longer tolerate John’s preaching ministry. She ordered him deposed and forcibly sent into exile. Yet in an amazing twist of Providence, Eudoxia changed course and had him reinstated as Bishop. Some say this was entirely due to the fierce protests of the common people who loved Chrysostom’s preaching. Others state that a sudden earthquake immediately following his exile put fear into her heart. Whatever the cause, Chrysostom was returned to the pulpit, more emboldened than ever to preach the word and to never give way to the fear of man.

A homily from this time sheds great light on the strength and source of Chrysostom’s convictions. It is worth quoting in full:

“Walls are shattered by barbarians, but over the Church even demons do not prevail. And that my words are no mere vaunt there is the evidence of facts. How many have assailed the Church, and yet the assailants have perished while the Church herself has soared beyond the sky? Such might hath the Church: when she is assailed she conquers: when snares are laid for her she prevails: when she is insulted her prosperity increases: she is wounded yet sinks not under her wounds; tossed by waves yet not submerged; vexed by storms yet suffers no shipwreck; she wrestles and is not worsted, fights but is not vanquished. Wherefore then did she suffer this war to be? That she might make more manifest the splendour of her triumph.

Ye were present on that day, and ye saw what weapons were set in motion against her, and how the rage of the soldiers burned more fiercely than fire, and I was hurried away to the imperial palace. But what of that? By the grace of God none of those things dismayed me. Now I say these things in order that ye too may follow my example. But wherefore was I not dismayed? Because I do not fear any present terrors. For what is terrible? Death? Nay, this is not terrible: for we speedily reach the unruffled haven. Or spoliation of goods? “Naked came I out of my mother’s womb, and naked shall I depart” (Job 1:21); or exile? “The earth is the Lord’s and the fulness thereof” (Ps. 24:1); or false accusation? “Rejoice and be exceeding glad, when men shall say all manner of evil against you falsely, for great is your reward in Heaven” (Mt. 5:12).

I saw the swords and I meditated on Heaven; I expected death, and I bethought me of the resurrection; I beheld the sufferings of this lower world, and I took account of the heavenly prizes; I observed the devices of the enemy, and I meditated on the heavenly crown: for the occasion of the contest was sufficient for encouragement and consolation. True! I was being forcibly dragged away, but I suffered no insult from the act; for there is only one real insult, namely sin: and should the whole world insult thee, yet if thou dost not insult thyself thou art not insulted. The only real betrayal is the betrayal of the conscience: betray not thy own conscience, and no one can betray thee.”[1]

Sadly, Chrysostom’s return to Constantinople was short-lived. He was banished by Empress Eudoxia the following year (404). For three years, he lived in exile, writing letters to his congregation in Constantinople, until Eudoxia decided that John should be banished to an even more remote location where any regular communication with the imperial capital would be nigh impossible. Chrysostom was force-marched through inclement weather until his body broke under the strain and he collapsed from sheer exhaustion. He died on September 14, 407.

Legacy

Thirty years following the death of Chrysostom, Eudoxia’s son, Theodosius II, now the Emperor, publicly denounced his parents’ sins in their persecution of the godly Bishop Chrysostom.

To this day, Chrysostom's life continues to serve as an enduring testament to God's transformative work through a fearless preacher who unapologetically proclaimed His word.

[1] Phillip Schaff, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series, vol. 9, p. 14.